I have often mused about Anita Brookner's personal life. Partly because she kept it largely out of the public gaze while she was alive and partly because it's hard to read her output and not jump to conclusions about her private life and personality. This is a sloppy approach to understanding a novel for sure, and I have done it less and less as I make my way through these re-reads of her novels, finding far more depth and breadth in her characters than I did the first time through. But, I must admit, as I read Incidents in the Rue Laugier, I found myself sliding back into wondering about how dire and depressing Brookner's life must have been to have written these characters and this story.

On the surface Maud Harrison (née Gonthier) is someone completely stuck in a reality defined by others. Her mother, her lover, her husband, and her in-laws. At no point does Maud seem to have any agency. At an early age her fate seems sealed by situations seemingly out of her control. As I silently urged her to find her feet I began to think again about how this must be a reflection of Brookner's life. But as Maud lamented her lack of independence and freedom, it occurred to me that Anita Brookner was not one of her characters, indeed she was the antithesis of her characters. Her life, at least from the outside, was nothing but an exercise in independence and freedom. She made significant inroads in the male bastion of her academic career, she upturned her academic life at age 50 to become a prolific novelist, and, as far as the public can see, was never encumbered by romantic relationships that so often prove so stifling to her characters.

In Incidents in the Rue Laugier, Maud's mother Nadine is focused on finding a suitable way to get Maud married off as soon as possible. When they go to Nadine's sister's place for their summer holiday Maud is introduced to her cousin Xavier's English friend Robert Tyler and to his college friend Edward Harrison who has been invited to help make up numbers for tennis. There are actually spoilers in this Brookner so I am going to skip over a few things and just say that Maud and Edward end up marrying. Neither really want it but neither seem to have the will to make anything else happen. Time and again there are suitable opportunities to call it off but both lack enough imagination to come up with any alternative plans for life.

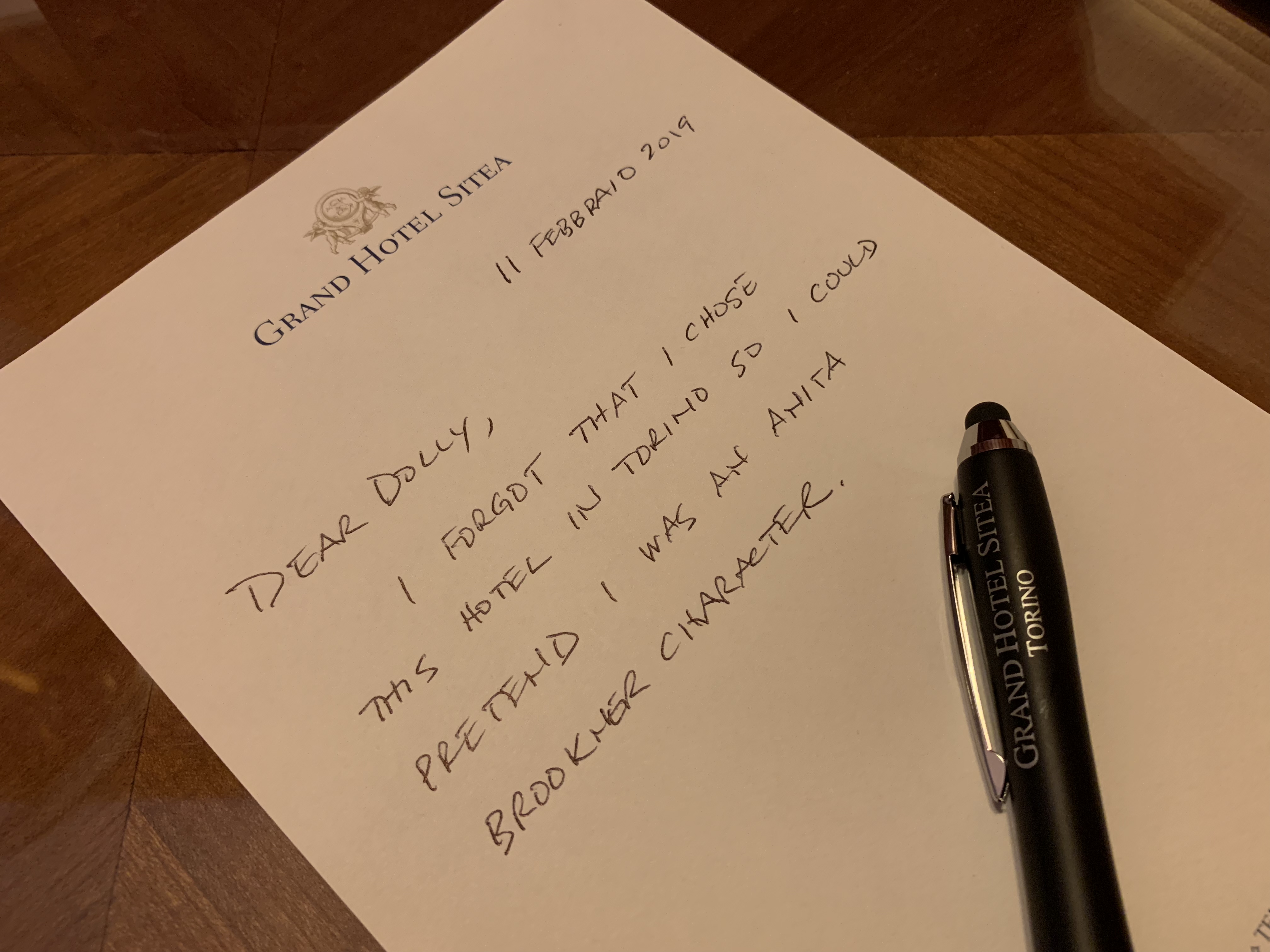

For the most part I have no problem speaking my mind and am often honest to a fault. But what I have realized over the years is that sometimes I work through issues in my head and forget that I haven't shared that process or outcome with others. The result then in those circumstances is not un-Brooknerian, leading to missed opportunities, confusion, miscommunication, mistaken impressions, and even bad feelings. When discussing one of the most consequential moments of her life, Maud asks her mother why she didn't warn her or try and save her from a bad situation. Nadine's response?

We were at dinner, if you remember. Nobody argues at the dinner table.I would never let something as trivial as that keep me from an important discussion, but my own communication foibles can have the same result. For myself, whatever challenge I may create or find myself in I tend not to let them add to any sort of cumulative inevitability. One of the glories of adult life is the ability to redefine or reset your own destiny even if within broader constraints. But for Maud and Edward and most everyone else who ambles across the pages of Incidents in the Rue Laugier inertia is an unalterable functional reality.

Brookner chooses an uncharacteristically unconventional narrative approach. The novel begins and ends with Maud's daughter Mary finding her mother's notebook after her death. She tells us right off the bat that she is to be our unreliable narrator as she launches into Maud's life story. What we don't find out until the end is just how little real information that notebook offered and that what we have been reading is more or less pure fantasy on Mary's part.

But it is also true that most lives are incomplete, that death precludes explanations...But that notebook serves as a reminder. Its lesson--that any notation, any record, is better than none--tells me that life is brief, and also that it is memorable, that the trace it leaves behind is indelible. And if the trace is inscrutable, this too may be appropriate. The dead, perhaps even more than the living, have a right to their mysteries. And who knows? We, the survivors, may be called upon to explain them, if only to ourselves.